- Home

- Yasmin Hamid

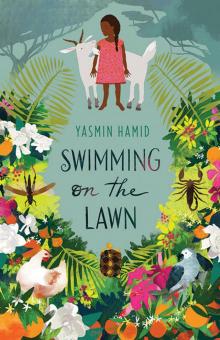

Swimming on the Lawn

Swimming on the Lawn Read online

Yasmin Hamid grew up in East Africa with her siblings, English mother and Sudanese father. She loves reading and has been in the same book club group for almost twenty-five years. She is happily married and has lived in Western Australia since 1988. This is her first novel for children.

for my family on four continents

and especially for Nigel

Khartoum, Sudan

1960s

The Picnic

Everyone is crammed in the car: four kids on the back seat, Mama and Dad in the front. Food, folding chairs, and table are squeezed into the boot, with a rug and towels stuffed into the gaps to stop any rattling. I am sitting in my usual place in between Amir, who is by the window behind Dad, and Sami, who is next to Selma.

‘Mama, can you tell Selma that it’s my turn to sit by the window? She sat by the window the last two times.’ Sami is using his most grown-up voice, so he can’t be accused of whining.

‘Just be still, the lot of you!’ Dad’s tone is a warning, so everyone keeps still and silent for what is probably less than a minute.

Sami elbows Selma’s arm hard. Selma rubs her bruise and glares at him, momentarily jutting her jaw and baring her lower teeth to let him know she will get back at him as soon as they are alone.

Sami stares back then slowly crosses his eyes to show her he doesn’t care.

I am wearing my dark blue swimming costume under my yellow and white striped frock, and I am hot and sweaty. The air coming through the wound-down windows is dusty and smells of exhaust fumes.

The roads are full of traffic and it is slow moving. Every few minutes someone tries to overtake and gets so close to our car that Dad keeps tooting the car horn, and swerving. At each crossroads, there is so much commotion and uproar that he waves his arm out of the driver’s side window and shouts, ‘Ya himaar! You donkey!’ And sometimes, for what I assume is a different annoyance, he yells, ‘Ya ibni kelb! You son of a dog!’

Mama looks out of her window and doesn’t seem to hear, but I see her mouth twitch when she hears Sami mimicking Dad in a low voice. This time she doesn’t turn round and tell him to behave.

I shake my head at Sami, as a silent warning to stop. He is likely to continue until he gets us all into trouble.

At last we leave the noise of the town behind and we pass mudbrick houses, an expanse of stony desert, and then an occasional small house, sometimes no more than a single room. We call this ‘the road to somewhere’, because we never know where we are going, but it is usually somewhere nice.

We play I-spy, to pass the time. When it is Mama’s turn, and she says, ‘I spy with my little eye something beginning with G,’ we know we have to think of really difficult things.

‘Garage,’ says Selma.

‘Where?’ asks Sami.

‘No,’ says Mama.

‘Where did you see a garage?’ Sami persists, but gets no answer.

‘Gravel,’ says Selma.

‘No,’ says Mama.

‘Gas tank,’ says Sami.

‘That’s a good one, but no.’

I look around. There is no point saying ‘girl’ or ‘gate’ or ‘green’ (the colour of our car).

‘Groove,’ says Selma.

‘What’s a groove?’ asks Sami.

‘It’s like a long, narrow cut. Selma probably meant the groove you can see around the car door.’

‘No, I didn’t. It’s the groove on Dad’s face next to his eyes.’

‘Well, I suppose his tribal scars do look like grooves. But no, that isn’t it.’

‘Gammar,’ I say.

‘Excellent,’ says Dad, smiling at me in the rear-view mirror.

‘That’s not fair,’ complains Selma. ‘You didn’t say anything about using Arabic words. And anyway I can’t see the moon from where I am.’

‘Don’t make such a fuss, and the answer isn’t gammar.’

‘Goat,’ shouts Amir, who is now bouncing on my lap.

‘Yes!’

We all cheer, and I give Amir a squeeze.

Soon we turn off the main road and onto a dirt track. The car shudders and jolts as we go from corrugations to soft sand and back to corrugations. The dust coming in the open windows is like thick brown smoke, but it is too hot to wind up the windows. We borrow Mama’s watch and take turns timing ourselves holding our breath while everyone else makes silly faces to break our concentration.

‘I am the winn-er,’ singsongs Sami.

‘So?’ says Selma. ‘It wasn’t even a minute.’

‘I am the winn-er,’ taunts Sami.

‘Trees!’ I say.

As soon as we see the acacia trees in the distance we know we are nearing the river. The trees look like green umbrellas: they only have leaves on top where the goats can’t reach.

As soon as Dad parks in the shade of a tree, we are out of the car and running down the bank to the water.

We hear Mama calling after us, ‘No swimming till I’m there.’

I take off my sandals and squelch my toes in the warm mud at the water’s edge. The river is wide and flat and blue. On the distant shore, smoke from the brick kilns rises in vertical lines up into the sky. Mudbricks are being baked to sell in the town. I look up and see a few hawks circling slowly, high in the sky. There is no breeze, but it feels cooler now that we are near the water.

By the time Mama arrives, carrying our towels, we have undressed and are waiting impatiently.

‘In you go, then,’ says Mama. Selma, Sami, and I plunge in, but even though we can all swim we stay in the shallows, and start splashing and throwing handfuls of mud at each other. Amir stays with Mama and plays on the bank, and collects stones and pretends they are cars.

When it is time to eat, we rinse the mud out of our hair and wash our arms and faces before Mama gives each of us a towel to wrap around our shoulders. Our feet are still wet, so we carefully pick our way to the car while Mama carries Amir as well as our clothes and shoes. The rug is laid out, and Dad is in his chair reading the paper.

We sit on the rug with our dirty feet off the edge, and Mama passes us cups of water and slices of watermelon. As I eat, I notice three children hiding behind one of the nearby trees. They take turns peeping at us and giggling. Mama notices them and waves them over, but they shake their heads. After a while I see that they have moved to a tree closer to us, and not long after that they make it to the other side of the car.

Mama approaches them with a plate of watermelon, and leaves it on the bonnet of the car. When she comes back and sits in her chair, she turns it slightly so that her back is to the children.

‘They’re eating the watermelon,’ I whisper.

After we finish our picnic lunch, and have packed away the crockery and leftover food, Dad falls asleep in his chair, and we play a noisy game of snakes and ladders.

Cotton

There is no school during the hottest months – which is just as well, says Mama, because the crowded classrooms are incubators for infectious diseases.

I love the school holidays. We go swimming with friends in the afternoons, and then come home to cups of tea and fresh bread sticks spread with butter and jam. The best thing is there is no homework, so there is extra time for reading between feeding the chickens and collecting the eggs, helping Mama in the kitchen, or going to the shop.

In the mornings I usually stay in bed reading until breakfast at ten o’clock. But today we have to be up at seven. While Sami and Selma go with Dad to the market to see if they can buy a goat, Mama and I strip all the beds in our room of their sheets, and I help her drag the mattresses out to the verandah.

It is already hot, and I can feel the sweat running down my chest, and my ponytail is stuck to the back of my neck.

; ‘Let’s have a cold drink,’ says Mama. ‘Oh, and Farida, dear, before you come in, could you let the chickens out. I haven’t had time this morning.’

I go around the side of the house, past the servant’s room and shower, through a hedge, past the pigeon loft, and open the wire gate to the chicken run. The chickens rush past me, just like the boys from the high school all trying to get off the bus first. With the rooster leading, the chickens make for the irrigation ditch that runs alongside their pen, squeeze under a hedge, and disperse into one of the garden borders where they like to scratch and feed in the safety and shade of the bushes.

I have just reached the kitchen door when I hear clapping by the gate.

‘The mattress man must be here,’ says Mama.

I follow her onto the drive. Just inside the open gate, we see a man, a woman, and two children. The man and woman both have huge sacks on their backs, and the older of the two children has a cloth bag slung on a long strap over his shoulder.

‘Sabah al khair. Good morning,’ says Mama. ‘Come in. The mattresses are on the verandah.’ The family follows us back to the house.

Once on the verandah, the couple put their sacks down in the corner. Then the man squats next to one of the mattresses, and with a sharp knife slits it open down its whole length. The cotton puffs out like popping corn. The children go over and start pulling out all the cotton and piling it in a big heap.

‘Can I help?’ I ask Mama.

‘No,’ she says. ‘It’s their job and they know what to do. You sit on the kitchen step and watch, and I’ll get everyone a drink.’

By now the children are emptying the second mattress. The pile of cotton is huge. It isn’t white like the cotton balls we use for putting Dettol on our cuts, but pale brown, and lumpy with little black seeds. It looks like a hill of boiled potatoes covered with flies.

The mother comes over and takes one of the empty mattresses and lays it onto a bolt of thick cream fabric. After some measuring, she cuts lengths of material for the new mattress covers, then with a very big needle and strong thread she hand-sews the fabric into three large bags, each one with a short side left open.

All the cotton is on the floor now, and the man and his children are beating the heap of cotton with long sticks.

Mama comes out of the kitchen carrying a tray with four glasses and two jugs, one with homemade lemonade and one with cold water, and puts it down on the floor next to the woman. I go over and pour lemonade into two of the glasses for the children. They stop beating the cotton and watch me as I place the drinks on the floor by the wall where they won’t get knocked over. I point to the children and then at the glasses of lemonade. The children look at their dad and he nods. They put down their sticks and pick up their drinks. I look at the sticks and can’t stop myself from picking one up and giving the heap of cotton a wind-whistling whip. As I lift the stick again, bits of cotton cling to the end, flick off, and float gently around me. I wonder if that is what snow is like. As I keep whacking the pile, it gets harder to breathe, and my eyes are itching, and I keep sneezing, and the children laugh. I’m sweating again and my arms are covered in white fuzz. This isn’t as much fun as I’d thought. I drop the stick on the floor.

I go into the house, have a shower and put on a clean frock. I go to the kitchen where Mama is preparing breakfast. I lift the tablecloth and see Amir playing under the table. ‘Do you want to come and help find some eggs?’ Amir crawls out and I pick him up. ‘Let’s see how many we can find.’

The chicken run is cool and quiet. We look in the nesting boxes and find four eggs. I set Amir down, and I hold out my skirt so that he can carefully put the eggs into it.

‘How many have we got, Amir?’ I say. ‘One.’

‘Two,’ says Amir.

‘Three,’ we say, together.

‘Four!’ we shout.

‘Let’s take these in and put them in the fridge, and then you can see our new mattresses being made.’

We have just put the eggs away when I hear tyres crunching on the drive.

‘Dad’s back!’ I run out to the car. Selma and Sami are both making faces at me from the front passenger seat, and I can hear a terrible crying coming from the back.

‘We’ve got the goat,’ shouts Selma.

‘And it’s done a poo in the car,’ shouts Sami.

I look in the rear side window and see a little goat on the floor in front of the back seat. All four of its legs are tied together. Our eyes meet, and I know we are going to be friends.

Redecorating

One morning, about a week later, I’m in the bathroom cleaning my teeth when the workmen arrive.

I hear a big truck pull up on the driveway. I run out onto the verandah. One of the men is rolling a huge metal drum along the truck bed to the tailgate. Two other men lift it down and carry it over towards the nearest neem tree. Another man puts the end of a hose into the drum and turns on the water.

Dad comes out of the front door with Mama.

‘Dad, what’s in those big paper sacks? Is it cement?’

‘No, it’s lime. We are having the inside of the house painted. They’ll be doing your room first. You can watch, but don’t get in the workmen’s way.’

‘Come and get your cup of tea,’ says Mama. ‘It’s made.’

As I follow Mama to the kitchen, I see that the French doors to our bedroom are open, and that our beds are being carried out to the garden and left on the lawn. Amir is dozing in his highchair, and Sami and Selma are already sitting at opposite ends of the kitchen table. They have both slid down onto the front edge of their chairs, one foot on the floor and the other foot kicking, trying to reach each other under the table. When they see us they sit up and each of them picks up their teacup and has a sip, copying each other’s movements as though they are looking at their reflection in a mirror.

The previous week, Dad had got very angry, and had pointed to each end of the table and shouted, ‘I’m sick of the pair of you! You will sit there and nowhere else, and you will carry on sitting there until you start behaving properly or are old enough to leave this house! Do – you – understand?’

Sami and Selma had both nodded, and Amir was so frightened that he started to cry, and Mama had to get up and carry him into the garden. I had watched through the open kitchen door as she twirled with him in her arms until he smiled.

‘The painters are doing our room first,’ I say to Selma.

‘So?’ she replies.

‘Maybe we can choose what colour we want,’ I say.

‘I don’t care. It’s only a silly wall.’ And turning to Mama she says, ‘Me and Sami – I mean, Sami and I – have finished our tea and we’re going to play on the swing.’

‘Stay away from the workmen,’ says Mama who is looking in the fridge, but they have already gone.

‘Farida, do you want something to eat or can you wait until breakfast? It’ll probably be a bit late today.’

‘I’m okay,’ I say. ‘I’ll have one of Aunty Miriam’s biscuits. Mama, what colour is our room going to be?’

‘We don’t have much choice. All the ceilings and the top quarter of the walls will be white. The only colours we can choose from are yellow or green. I thought we’d have a medium yellow in the kitchen, and a very pale yellow – almost cream – in the sitting and dining rooms and our bedroom. What would you like in your room? How about a very pale green? That will look lovely and cool. I’ll have to make sure the painters don’t put too much green powder in with the white.’

After I finish my tea and biscuits, I pick up Amir and put him on my hip and we go out to watch the workmen. One man is tipping a bag of lime into the drum of water while another man stirs with a long wooden pole. I can hear the mixture hissing. Another bag is tipped in. The man stirring gets tired, and another man takes over. When the lime is dissolved I go closer, and Amir and I peep over the rim. It looks like milk. The arm holding Amir accidentally touches the side of the drum. It burns. One of the men not

ices me jerking away. ‘The water gets hot when you put lime in it,’ he says to me. The other men watching us hear this and laugh.

I turn away and cross the drive to the side garden and we go to see the goat. He is tethered to the trunk of a small tree and he runs towards us trailing his rope. His black eyes always look hopeful when he sees me, and he nudges his nose at my arm looking for a treat, though he still has a small pile of fresh green feed next to his bucket of water. I always try and check on him if I’m going past as he sometimes manages to go round and round the tree, winding the rope so short that he can’t move. Today, I make sure Amir is at a safe distance while I untie the goat and then we take him for a walk round the back garden. The goat pulls ahead on the rope and I have to keep him away from the rosebushes and Mama’s flowerbeds, but I let him nibble at the hedge. He delicately plucks leaves from around the thorns and chews greedily, his little upturned tail twitching from side to side. The goat is so preoccupied that Amir bravely gets close enough to stroke the smooth, shiny hair on its flank, before quickly retreating behind my legs. As we walk alongside the hedge I can hear Sami and Selma shrieking and laughing at the tops of their voices. When I reach the archway onto the lawn I see that they aren’t on the swing but are jumping on our beds, the metal springs squeaking in protest. All three beds have been lined up next to each other and Sami and Selma are bouncing from one bed to the other, and whenever they happen to bounce onto the same bed at the same time, they find it difficult to keep their balance.

‘You’d better take your shoes off before Dad sees you,’ I yell at them, as I lift Amir onto the swing seat and look around for a safe place to tether the goat.

Glue

Our kitchen table is covered with scraps of paper, pieces of card, and coloured pencils. Selma and I are making new clothes for our paper dolls. A few months ago our English Granny, Mama’s mother, sent us two books from England, each with a doll to cut out printed on the back cover. The inside pages were printed with dresses, skirts, blouses, and hats that we have already cut out with scissors. We bend the tabs that are on the shoulders and waists of the clothes to dress our dolls. The dolls have their left hands on their hips, so the crook of their elbow makes a convenient hook for a handbag.

Swimming on the Lawn

Swimming on the Lawn