- Home

- Yasmin Hamid

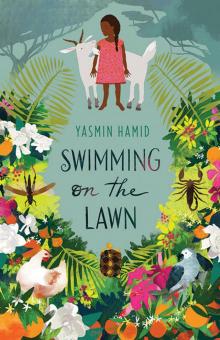

Swimming on the Lawn Page 9

Swimming on the Lawn Read online

Page 9

‘Nothing.’

‘But I saw you talking.’

‘It isn’t important.’

‘Yes, but what did he say?’

‘He just asked how Dad is.’

‘No he didn’t. Why won’t you tell me?’

‘I just did.’

‘You’re just saying that because you don’t want to tell me. If that’s all he said, why didn’t you just say so in the beginning?’

‘I didn’t, because it isn’t important.’

‘You’re lying.’

‘No I’m not.’

‘Yes you are.’

I can see that Selma is about to cry, but I can’t think of anything interesting that I can pretend was the subject of our conversation.

At that moment Grandma comes in, rattling the tray as she puts it down on the draining board.

‘Is the tea ready?’ she asks.

‘Yes,’ says Nadia.

She pours boiling water into the rinsed-out teapot. I would never have guessed that most of the boiling water was going to be used for making tea.

‘What’s happening, Grandma?’

‘Things have started to move along at last. A few sips of this tea and your mother should be ready to have the baby in an hour or so. Put on another saucepan of water to simmer for now.’

A whole hour!

The New Baby

‘It’s too hot in here. Let’s find everyone and make a list of names,’ suggests Nadia. We follow her out the door into the backyard. The younger brothers are now taking turns throwing stones at a stack of old, broken terrazzo floor tiles that they have built into a wobbly tower. Each time a stone hits its target the tower wobbles, but doesn’t fall.

‘Can we have a go?’ I ask.

They agree as long as we stand a couple of metres further back. We run around hunting for stones, and soon we have a decent pile at the ready. We queue up behind our line and wait for the boys to take their turn first. Between them they manage to wobble the stack a few time, but fail to make it collapse.

Now it’s the girls’ turn. We all miss as we try to gauge the distance and the force needed. In the second round, the boys manage to knock off one tile for one point. The tile is put back on the stack for our turn. Selma hits the stack and makes it wobble, but fails to score. Azza hits the stack halfway down and knocks four tiles off for four points. The girls cheer.

The tiles are restacked and both Nadia and I miss. After ten rounds, the boys have taken the lead 7–5.

While the boys are in front and in a good mood, Nadia suggests they tell her the baby names they have chosen. We end up with nine names for a boy, but only four for a girl. The boys are confident the baby will be a boy.

Not wanting to play any more, the whole gang troops back to sit outside the bedroom door. No sounds can be heard other than the murmur of low voices. A few minutes later, we hear a baby cry, and we all cheer. The door opens and Grandma calls out to Nadia’s father, ‘It’s a boy. Praise be to Allah!’ The bedroom door closes. The brothers are so excited that it is another boy, they all get up and start chasing each other up and down the verandah until they are told off by their father.

‘Some more tea, Nadia,’ he calls. We get up and go to the kitchen. We are disappointed it isn’t a girl. Nadia fetches a pencil and a piece of paper and writes out the list of boys’ names for her mother, while Azza makes the tea.

‘Can I carry the tea out to your dad?’ asks Selma.

‘Of course you can,’ says a smiling Azza, thrilled to be let off her turn.

Grandma comes into the kitchen carrying a bundled-up bedsheet that is stained with blood. ‘Put this to soak in a bucket of cold water,’ she says, handing it to Nadia. Then the midwife comes in, holding the saucepan that was used to boil her instruments.

‘And this is to be buried,’ she says, handing me the saucepan.

‘Can I see?’ says Selma.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘But first you’d better carry out the tea, before we get into trouble.’

When Selma gets back, she looks into the saucepan that is on the draining board. ‘Yuk. Looks like raw liver. What is it?’

‘I can’t remember what it’s called, but it’s what feeds the baby when it’s inside the mum. You see that long bit that looks like a rope? You know, the cord. One end grows into the baby’s bellybutton to feed it.’

‘What do you mean, grows into the baby’s bellybutton?’

‘Oh, I don’t know, maybe it doesn’t grow into the bellybutton, but it’s joined up to it somehow, and when the baby is born, the midwife cuts the cord because the baby will drink milk from the mum once it’s out. And that thing there isn’t needed any more, so it comes out after the baby.’

‘But what if there is another baby in her tummy. How will that one get any food?’

‘If that happens a new one will grow to feed the new baby.’

Selma points at the saucepan, and says, ‘But why doesn’t that just stay inside and get used again?’

‘Because all the food in it is used up. And anyway the tube has been cut, so it can’t be used again.’

Nadia and Azza have been listening to us and they are trying not to laugh.

‘Anyway, stop asking so many questions,’ I say. ‘We can ask Mama when we get home.’

Nadia picks up the saucepan and we follow her out to the yard, where we watch her tip everything into the hole. Then Nadia takes a handful of dirt and rubs it around the inside of the pan to scrub it clean. We all help to fill in the hole. There’s dirt left over so we make a mound over the top. We stand around admiring our work and Selma decorates it with a pattern of small stones.

Back in the kitchen, Nadia scrubs the now shiny saucepan with soap and water, and after rinsing it and pouring in a few centimetres of water she sets it on the stove, lights the gas, and puts a lid on the pan.

‘When can we see the baby?’ asks Selma.

‘Grandma will come and tell us,’ says Nadia. ‘We’ve been working hard: let’s have some tea.’

She doesn’t bother with the teapot. She puts a couple of teaspoons of tea-leaves into a small saucepan, and pours boiling water over them from the saucepan that didn’t have the afterbirth in it, then adds a few spoons of powdered milk from a tin, and puts the pan on to boil. When the milky tea starts bubbling, she turns the gas down so that it simmers while she washes the used tea glasses stacked by the sink. When she finishes, she lines four of them in a row on the tray. Turning off the gas, she pours the tea through a strainer until each glass is two-thirds full.

‘Help yourselves,’ she says. I pick one up by the rim and put it on the draining board to cool a little. Nadia and Azza put several teaspoons of sugar in their tea, before taking a cautious, noisy sip. I see Selma spoon some sugar into hers, but don’t say anything. We never have sugar in our tea at home, but Selma thinks it is unfair and always tries to sneak some into her tea when Mama isn’t looking.

Just then, Grandma comes into the kitchen smiling.

‘You can come and see the baby now,’ she says. ‘But we won’t tell your brothers yet. We can’t have you all in at once.’

We follow her into the bedroom, which seems dark, but after a few seconds my eyes adjust. A little light is coming through the slats of the wooden shutters. We go up to the double bed where Nadia’s mother is lying. She is covered from her legs up to her now-flat stomach by a thin shawl, and she is smiling at us. The baby is on the bed beside her, and it is tiny.

Wearing nothing but a thin cotton gauze singlet, and lying on his back on some folded fabric, the half-naked baby is fast asleep.

‘Why hasn’t he got a nappy on?’ whispers Selma.

‘Because he doesn’t need one yet,’ I whisper back.

‘But what if he does a wee? The bed will get wet.’

‘I don’t know,’ I say, keeping my voice low so as not to wake the baby. ‘Maybe they’ll put a nappy on when he wakes up.’

‘He might do a wee while he’s asleep,’ say

s Selma, forgetting to whisper.

Nadia’s mum smiles and says, ‘I’ll make sure he doesn’t wet the bed.’

He has tiny fingers, and a small face, and his closed eyelids seem smaller than those of my doll Annabel, and he has curlier eyelashes. His thick black hair is still damp from his first bath.

‘I’ve written a list of boys’ names on this paper,’ says Nadia, and she hands it to her mother.

‘Let’s see. They are all good names. I think we’ll call him Jamal.’

‘I chose that name!’ Selma squeaks with excitement and jumps up and down.

‘Shhhhh,’ says everyone else.

Swimming on the Lawn

Selma and I are walking home from school one day when we hear a loud bang, and what sounds like gunfire in the distance. We stop and turn towards the noise and we see black smoke in the direction of the market, but it is hard to tell how far away it is.

‘What’s that?’ Selma asks.

‘Perhaps it’s celebrations,’ I say, not wanting to frighten her. ‘But we’d better hurry. Can you run?’

By the time we get to our gate we are out of breath and sweating. We slow to a walk once we are on our driveway, and I notice that the lawn is flooded with water. Mama has heard the crunching of our feet on the gravel and is waiting for us at the kitchen door. ‘Are you okay? I was really worried. I was about to send the servant to look for you.’

‘What’s happening?’ I ask.

‘I’m not sure. I’ve got the radio on, but there hasn’t been any announcement. Your father hasn’t rung from work, so it probably isn’t serious.’

Selma, who is looking towards the garden, says, ‘Can we please swim on the lawn? Just this once? Please. We are so hot from all that running. We’ll be really careful.’

‘No. You are much too old now. Go and have a shower and get changed and then we can all have some cold karkadeh, and you can tell me what you did today in school.’

Selma and I get clean dresses and underwear out of our wardrobe and go into the bathroom. ‘You go first, I’ll sit here and decide which book I’m going to read next,’ Selma says. She puts a pile of books on the floor, and hangs her dress on one of the knobs on the big metal chest of drawers where the spare towels and toilet rolls are kept. In the top drawer, Mama keeps her bits and pieces, like the lipstick she only puts on for parties, a few pieces of jewellery that she never wears, her hairbrush and hairgrips, and the new box of sanitary towels and elastic belts she has bought for ‘when I am a bit older’. Mama always says most things are easier to cope with if you are prepared.

I stand under the shower, and think of how the water on the lawn looks like a lake. The mown grass clippings float on its surface in clumps, like mini islands for the ants to wait on until the water goes down. Every two weeks, water is pumped along channels to the fruit trees in the back garden, and then along the flowerbeds and shrubs in the front garden, and finally onto the sunken lawn which ends up with about fifteen centimetres of water over it. When Selma and I were little, we would put on our swimming costumes and ‘swim’ on the lawn, trying to keep away from the ants on their rafts of grass cuttings. The water wasn’t deep enough for proper swimming, so we usually ended up chasing each other and throwing clumps of soggy clippings at each other’s backs. The water soon turned muddy brown and Mama would make us rinse ourselves with the hose before we could shower in the bathroom. Swimming on the lawn was stopped when the gardener complained about the extra work of rolling the grass to even out all the holes and lumps we’d gouged during our half hour of fun.

‘I’m going to read Oliver Twist,’ Selma says. ‘Hurry up.’

I turn the shower off and step out. ‘Did you get that from the library?’

‘Yes.’

‘We’ve got Oliver Twist already,’ I remind her. ‘You know that Dad has got a whole set of Charles Dickens.’

‘I know, but this one has bigger print and I don’t have to sit at the table to read it. I can read it in bed.’

When we sit down at the kitchen table, our wet hair combed and our books in front of us, Mama pours our drinks.

‘I’m hungry. What can I eat?’ I say.

‘Shush a minute,’ says Mama, and she turns up the volume on the radio. ‘I want to listen to the news.’

The Health Check

The sun must be just starting to rise above the horizon. I know this because as Dad stops the car outside our school and Selma and I get out, we are ambushed by the flies that have spent the night in the nearby rubbish pile. They attack us like a well-prepared army, landing on our faces in the hope of breakfast. Waving off Dad and the flies at the same time, we walk through the school gateway. I’m glad we haven’t had to walk to school today. Dad has to inspect a new building and our school is on the way to the site. I took this chance to bring five of my favourite books for my friend Hibba to borrow.

Selma’s friends are waiting for her, and they call out to get her attention. ‘See you after school,’ she says to me, and swings her bag as she skips towards them.

I walk carefully across the playground, trying not to get dirt and stones in my sandals. I pass a group of girls bent over, all in a line, sweeping the sand smooth with their bunches of dried palm fronds in their right hands, while their left arms are resting across their backs, the palms of their hands cupped towards the sky as though begging for a handout. I realise it will be my turn to be on sweeping duty in a couple of weeks, and I’ll have to be at school almost an hour earlier than usual.

I make my way past the teachers’ office and onto the verandah in front of my classroom. The window shutters are always open to let in light, and the breeze – if there is one. There is no glass in any of the windows to keep out the flies, and there are no fans for when it gets hot. I can see one of the girls wiping the blackboard with a wet cloth. The old faded grey paint looks black and shiny where it is still damp.

My friend Hibba hasn’t arrived yet, so I put my bag down and lean against a verandah post and wait.

‘Fatima isn’t coming in today, and she’ll be away for quite a while,’ I overhear one of the older girls say to her friends. ‘Her mum’s ill after having another baby so Fatima has to look after her brothers and do all the cooking till her aunt can come from the village to help. Her dad doesn’t want Fatima to stay in school, but she’s really clever, and I promised to tell her what we’ve been doing so she can study at night after her brothers are in bed.’

‘Hi, Farida,’ Hibba says, as she gives me a friendly slap on the arm. I jerk away and feel my heart speed up in my chest. Hibba laughs. ‘How are you? Daydreaming, were you?’

‘I’m thirsty,’ I say. I pick up my bag, and we go off to the water room.

The water room stands across from our classroom by the only trees in the school. It has three walls – solid at the top and bottom, with fancy open brickwork across the middle at head height – and a flat corrugated iron roof. We step up into the open end. Each wall has a wide concrete platform at waist height with six round holes cut through the concrete. In each hole sits a big terracotta pot shaped like a giant wide-necked vase, and above each pot is a tap.

A girl climbs up onto the platform. She picks up a tin mug, dips it into the cool water in one of the big pots and drinks. When she has finished drinking, she tips what is left in her mug back into the pot and then jumps down to the floor. She holds out the mug to me and I take it. ‘Thanks,’ I say. After the girl has gone I put the mug back, climb up onto the platform, turn on a tap, cup my hand under it and drink. The tap water is warm. I watch as the water overflows my palm into the pot below. Mama says we aren’t to drink from the cup or pot because we might get ill from the germs of the other people using them. But whenever the older girls see me drink from the tap they tell me off.

‘Have you done all your homework?’ Hibba asks.

‘Yes. It took me ages to learn that poem off by heart, the phrasing is quite complicated. My dad had to keep correcting me. I got in such a muddl

e. But I practised in the car this morning and I remembered it all.’

The bell rings. Hibba and I line up with the girls from our class in neat rows. My favourite teacher, Miss Layla who teaches mathematics, stands on the verandah facing us, and when she is satisfied that we are all present and standing quietly, she points to the first row to lead the rest into the class.

In the room, I squeeze up onto a bench seat with two other girls behind a desk meant for two. There are sixty girls in my class. We all wear white dresses, and everyone has to have their hair tied back, either in plaits or a ponytail, but we are allowed to have any colour ribbons we like.

‘Good morning,’ says Miss Layla.

‘Good morning, Miss Layla,’ we singsong.

The bell rings for the end of class. Miss Layla says some students from the university have arrived at the school for a project they are doing on health, and our school is taking part. We line up on the verandah and watch as the first girl goes up to a table where she is given a form.

Soon it is my turn. The man at the desk asks my name, and ticks it off his list.

‘Aren’t you too young for this class?’ he asks.

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘My dad asked for special permission for my sister and me to start school at an earlier age, because we already knew how to read and write in English and he wanted us to learn Arabic as soon as possible.’

He writes my age on the form and hands it to me. ‘Take this to the lady over there.’

I go and stand on the weighing machine, but before I can see what the woman is doing, she gives me back my form, waves me away, and sends me to another line where, when it is my turn, I stand against a vertical ruler and a man lowers a piece of wood onto my head and reads off how tall I am.

After I’ve been measured, someone looks at my teeth, and then someone looks in my ears with a little torch, and another person asks me to cover my right eye and read the letters on a chart, and then to cover my left eye and do it all again.

After the eyesight test I am given a glass test tube. ‘We need a urine sample. Take this to the toilet and bring it back full, and don’t put any water in it’, says the man. I feel embarrassed, and holding the test tube next to my skirt, hoping no one can see it, I turn and walk towards the toilets. I walk very slowly and wonder if I will get into trouble if I don’t take the sample back.

Swimming on the Lawn

Swimming on the Lawn